Patricia Bernstein on the pros and cons of depicting real-life characters in historical fiction.

Contemporary critics have complained about novelists who depict characters of recent memory, even sometimes pretending to reproduce their thoughts without any proof that these people ever thought any such thing. In the novel Blonde, for instance, Joyce Carol Oates goes so far as to imagine thoughts recorded in the fictional diary of the character Marilyn Monroe. Oates’ novel was widely praised. But Guy Gavriel Kay, in an article in The Guardian, is offended by the very notion that a work of fiction can present ‘the true inner world of a real person’. ‘This is nonsense and it is pervasive,’ he says.

We who write about characters who lived safely many decades or centuries ago have a freer hand. The historical record that remains to us of real people, whether sparse or lavish, always leaves plenty of gaps that we can fill with imagination. I see no harm in this, as long as we acknowledge that we are writing what is clearly demarcated as fiction, not history. In fact, I believe the best historical novels can create little vignettes of moments in the lives of historical characters that historians could not possibly have gleaned from the factual record, but yet offer something of the vivid scent of the real man or woman.

Perhaps my all-time favourite historical novel is The Man on a Donkey by Hilda Frances Margaret Prescott (H.F.M. Prescott, as she is usually known). Prescott was an academic who spent her life steeped in the Tudor era. She is still known for a biography of Mary Tudor which won the James Tait Black Prize. She knew so much about the world of the Tudors that she wrote almost as if she had lived through the period herself. When you read The Man on a Donkey, you simply fall headlong into the early 16th century in England and don’t come up for air until the book ends.

In one striking moment in the novel, Prescott describes Henry VIII looking out of the window of Greenwich Palace to where Anne Boleyn is singing, sitting on the grass in the midst of a group of young courtiers:

The King turned at last from the window. He had a look as of a man who has opened a box to feed his eyes on the sight of a very rare jewel; now he had closed the box, but the glow and softness of delight were still on his face and a little private smile that faded quickly.

Who has ever done a better job of depicting the hunger of a married king who is totally besotted with a young woman? Perhaps besotted enough to change the world?

But what about those occasions when an author’s depiction of a real-life historical character violates what we think we already know, what perhaps we need to believe, about that person? In Becoming Benedict Arnold by Stephen Yoch, the author attempts to explain why the treason of a notorious historical villain was understandable or even worthy of forgiveness. Does he succeed in changing the reader’s ultimate estimate of the man?

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Stephen O’Connor’s surrealistic Thomas Jefferson Dreams of Sally Hemmings plays on the many faults exposed in recent years of one of the most exalted of the heroic U.S. Founding Fathers. In the novel, O’Connor even condemns Thomas Jefferson through the novelistic device of an imaginary diary written by Sally Hemmings, the slave who bore Jefferson several children over many years.

Whether or not we can accept and enjoy these revisionist approaches to history through fiction usually depends on our own individual judgment and taste. Our resistance can be stimulated by trivial deviations from our previous knowledge of a real-life character, as well as by wholesale reconstruction of historical characters.

I found myself shocked by Ariana Franklin’s (Diana Norman’s) depiction of the historical/mythical character of ‘Fair Rosamund’ in her novel The Serpent’s Tale. The real-life woman Rosamund Clifford, reputed to be a great beauty, was indeed a mistress of Henry II. However, an elaborate legend grew around the real-life story: King Henry, it was said, kept Rosamund in a secret bower protected by a labyrinth in the park of Woodstock Palace. But despite his elaborate precautions, his jealous queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, eventually found Rosamund and murdered her.

In The Serpent’s Tale, Fair Rosamund is poisoned by mushrooms. The protagonist of the novel, Adelia Aguilar, who is supposed to discover who killed her, is surprised to find that Fair Rosamund was barely literate, dull of mind and hugely fat—which challenged, to my mind, not only the legend but also the many Pre-Raphaelite paintings I have seen depicting a delicate, sylph-like Rosamund. The explanation offered in the novel as to why a powerful king married to a famous and fascinating beauty would keep a rather slow-witted, obese mistress on the side is that she relaxed him, like a ‘comfortable, bouncey mattress’.

Fair Rosamund by John William Waterhouse

My own discomfort with portrayals of historical characters that don’t fit our popular notions is especially acute when it comes to TV and films. I am aware that Showtime’s The Tudors was immensely popular, but, after seeing Henry VIII successfully portrayed by such monumental – and sizable – actors, such as Charles Laughton, Robert Shaw, and Ray Winstone, I simply could not accept a small, dark-haired actor, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, as a convincing Henry, no matter how many whiny temper tantrums he threw. Even Meyers himself admitted he was miscast as Henry VIII.

Similarly, I followed the Outlander TV series up to the point where the historical figure Bonnie Prince Charlie is introduced. The famously bold, handsome hero, subject of many folk ballads and tales of derring-do, the Bonnie Prince Charlie of legend, is portrayed in Outlander as a timid, nervous, anxiety-ridden creature whom no Scottish highlander would have followed across the street, much less into battle. At that point I was done with Outlander.

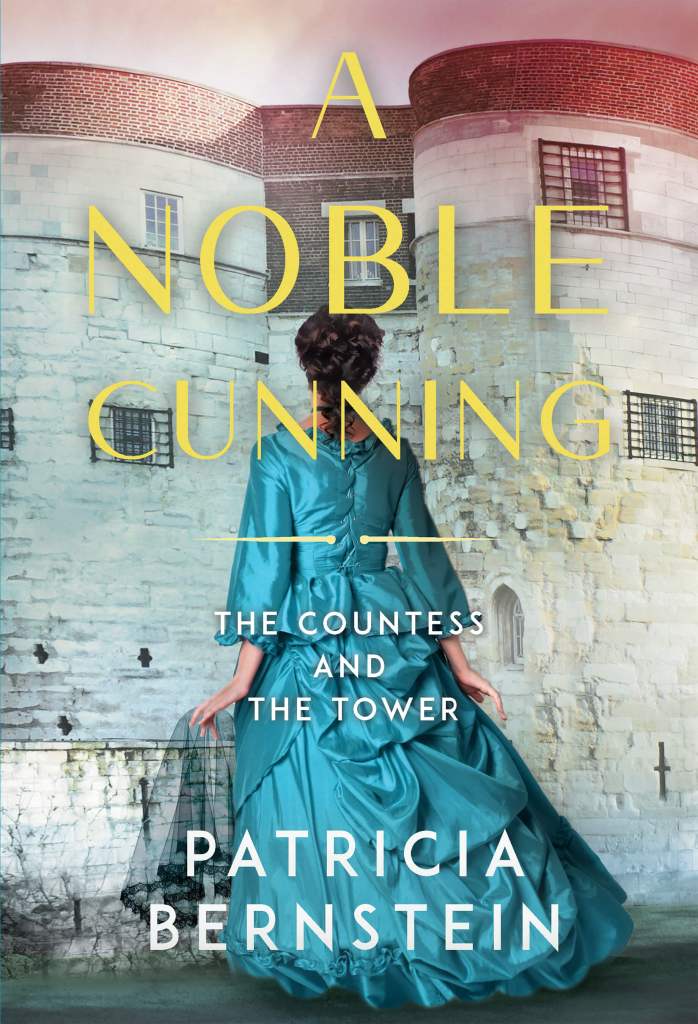

But I must admit I’ve been guilty of taking liberties with the historical record myself. My debut novel A Noble Cunning is based on the glorious, true story of the persecuted Catholic noblewoman Winifred Maxwell who rescued her husband from the Tower of London the night before his scheduled execution with the help of her women friends.

But, marvelous as the real Winifred Maxwell was, I determined early on in my research not to use the real names of the primary characters in the true story so that I could be free to introduce fictional elements into my novel. I hope my protagonist, Bethan Glentaggart, is a fairly close reproduction of the supremely intelligent and determined Winifred Maxwell. But I felt that the true story of Winifred had essentially a single primary villain, England’s first German king George I. I did not think that one villain, whom my heroine would encounter in person only once, would enable me to sustain dramatic tension throughout the novel. Fictionalising the story allowed me to add other villains to the tale: a fanatical, woman-hating Protestant ‘hedge preacher’, a virulently anti-Catholic guard at the Tower, and, most daringly, a self-centred and dissolute sister who must somehow be induced to join Bethan’s plot to save her husband.

Why, after all, do we choose to write historical fiction instead of historical non-fiction or biography? Well-written narrative history can be just as intriguing as fiction, after all. And most authors of historical fiction are not allergic to research. Many of us are fascinated by research. I have to constantly rein myself in from chasing every tantalising morsel of historical fact down every possible rabbit hole. I enjoy writing history and biography. But sometimes it is a great joy to leap the fence that corrals the pure historian and take our characters out into the wide, open world of imagination.

Patricia Bernstein was born in El Paso and grew up in Dallas. She earned a degree in American Studies from Smith College and taught English at Smith for four years before returning to Texas. In Houston she founded a public relations agency and published dozens of articles in media venues as varied as Texas Monthly, Cosmopolitan and The Smithsonian.

Her first book was Having a Baby: Mothers Tell Their Stories, a collection of first-person childbirth accounts from the 1890s to the 1990s. The second was The First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP about a horrifying “spectacle lynching”, which took place in Waco in 1916, and the young women’s suffrage activist hired by the fledgling NAACP to investigate the lynching. The third was Ten Dollars to Hate: The Texas Man Who Fought the Klan about the millions-strong 1920s Ku Klux Klan in Texas and across the United States. The book was a finalist for the Ramirez Family Award from the Texas Institute of Letters and was named one of the 53 best books ever written about Texas by the Austin American Statesman.

In 2023, Patricia Bernstein published her first novel with History Through Fiction, a traditional small press. The novel, “A Noble Cunning: The Countess and the Tower,” is based on the true story of Winifred Maxwell, Countess of Nithsdale, a persecuted Catholic noblewoman who, in 1716, rescued her husband from the Tower of London the night before his scheduled execution with the help of a small group of devoted women friends. The novel debuted as the #1 Amazon bestseller in Scottish Historical Fiction and a bestseller in other historical fiction genres.

Patricia lives in Houston with her husband Alan Bernstein where she sings with Opera in the Heights and other organizations, and admires the achievements of her three wonderful and very different daughters. A Noble Cunning is her debut novel, inspired by a story she heard during a visit to Scotland in 2014.

Leave a comment