Rebekah Simmers has been interviewing writers who are presenting at the HNS 2024 UK Conference

RS: We are so thrilled that you will be joining us for the HNS 2024 UK Conference! What are you looking forward to about the conference? Can you share a teaser for your presentation?

SGM: I’m really delighted to be coming to the conference and looking forward to it very much. It will be so good to hear fellow historical novelists talk about their craft, and to meet readers and hear about their interests and what they most enjoy reading. Am I allowed to say, though, that what I am most looking forward to is the trip to tour Agatha Christie’s Greenway? A bit of a dream come true. I’m going to be in conversation with Lisa Highton, who is my literary agent, and we will talk, amongst other things, about the arc of my career, the challenges of changing the type of historical novel I’m writing. I hope to quiz her on what agents really think, what puts them off and what they love.

S. G. MacLean will be in conversation with Lisa Highton at the HNS 2024 UK Conference

HNS has launched the First Chapters Competition with the conference. What is a novel you’ve read over your life that unexpectedly grabbed you from the opening lines and whose words stayed with you?

Oh, goodness – at the risk of being unoriginal, Wuthering Heights. I read it several times as a teenager and don’t think I ever quite got over it. Each of my main heroes in my own novels has, in his way, a little bit of Heathcliff in him.

I read that you have a PhD in History and that you began writing fiction while raising your four children – can you share a bit of that journey and how you managed it on your way to becoming an award-winning and best-selling author? Had you always wanted to write?

Clearing out a loft recently, I found a folder containing several chapters of a novel I began writing when my first child was a baby. I’d always wanted to write, but it was suddenly ‘disappearing’ as far as the intellectual world was concerned when I had a baby, as well as having another human being so utterly dependent on me. That made me carve out whatever little spare time I could to write. That novel was never finished, but by the time my third child was six weeks old, I’d completed and submitted my PhD thesis on education and poor scholars in 17th-century Scotland, and was taking the early steps of a planned academic career.

Family logistics, however, meant we had to follow my husband’s more reliable career and I found myself living in a rented farm cottage with mice running around everywhere and a baby who cried all afternoon. The only thing that would stop the baby crying was popping her in the car and driving her down to the seafront at Banff, the town we had moved to. She would be fast asleep by the time we got to the end of the farm road, and I would have half-an-hour or so to sit and look at the sea and think before it was time to collect the older two from school. That part of Banff has an old 17th-century harbour, the ruins of a medieval kirk and kirkyard, steep, narrow streets with evocative names and several surviving 16th- and 17th-century buildings. I wondered about the lives of the people who’d lived there centuries before me and that’s when all the types of characters I’d spent my research years studying in the archives came back into my mind and said, ‘We did’.

I bought myself a notebook and started to write the story that became The Redemption of Alexander Seaton, an historical mystery whose main character is a schoolmaster in a small northern Scottish town. I wrote when the children were sleeping, at nursery, at school, and on Saturday mornings when my husband would take them out for the morning to give me time. It’s possible that ours was not the most pristinely-kept house in the street. The book took four and a half years (one more child and three more house moves!) to write and a further 18 months and at least a dozen rejections to find an agent, but when I did get an agent, I soon secured three offers from London publishers. It was published in 2008 (when the crying baby was eight) and I have just completed my twelfth novel. Even though the children are all grown up and have left home now, writing is still my ‘me’ time, as well as being my full-time job.

Looking back on your own writing career, what would you say was the most influential writing advice you received from another author? How have you made that work for you?

The most influential writing advice I’ve received from another writer was many years ago, when I was about 17 and my late uncle, the thriller-writer Alistair MacLean, said, “If an editor ever tells you to change something, you change it. I never change anything, but that’s because I’m me. You change it.”

I’d say at least 95% of the time, I have taken that advice and my editor (Jane Wood at Quercus), who has an incredible eye for what works and what doesn’t, has always helped me mould what I give her into a better, tighter, book. Unfortunately, she doesn’t share my sense of humour, but I usually insist on keeping in at least one of my jokes.

Of the wide cast of characters in your novels, who has been your most surprisingly challenging character to write? Why? What strategies did you / do you use for these types of characters?

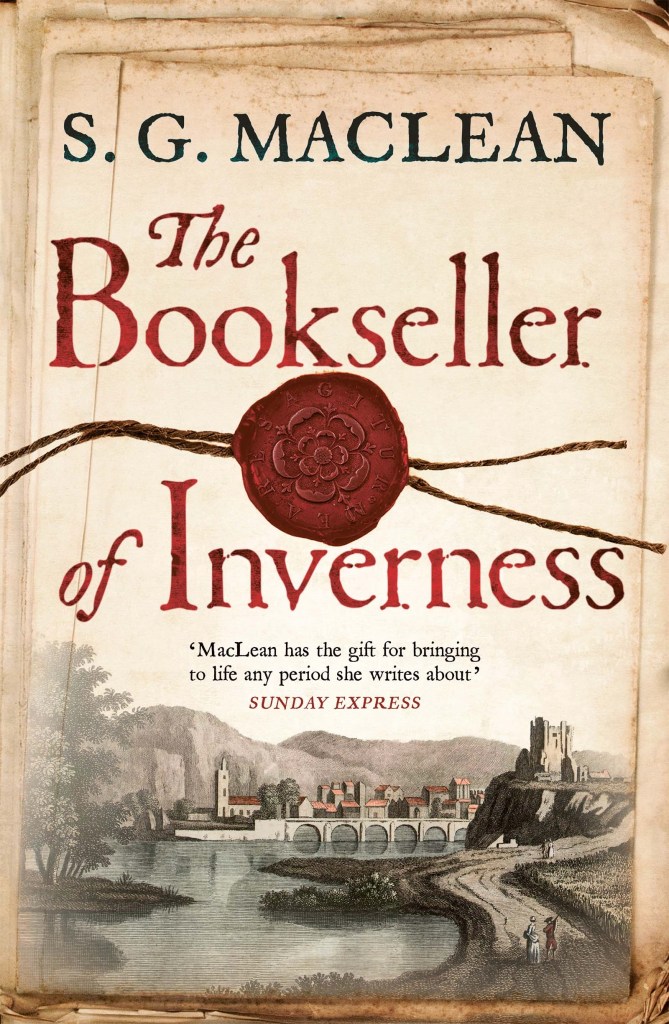

The most challenging character for me to write has been Iain MacGillivray, the main protagonist of The Bookseller of Inverness. That book was my first standalone after two series led by characters who were very distinct from one another – the introspective Scottish intellectual Alexander Seaton and the ‘takes no nonsense’ Cromwellian soldier and spy handler, Damian Seeker. Creating a main character sufficiently different from both of them was challenging.

Strangely, the thing I find helps most is finding the right name for a character. I know when I have the right name because of what it says to me about a person, and then I find their character comes more easily to me. Sometimes, also, I find thinking of a particular actor can unlock a character for me.

What do you think it takes to have longevity across a writing career? Sanity? Fun? What’s an unexpected joy that came into your life from such a successful career?

Listen to advice from people who know what they’re talking about.

Unexpected joys – too many to mention, but probably being asked to be the guest-speaker at the prize-giving at my own old school. In my head, I’m still the awkward, desperately-shy teenager who would almost be sick at the idea of speaking in public, yet life had taken me on a journey that meant I could stand confidently in front of a hall of 500 people and talk and smile and make them laugh. If 17-year-old me had been able to see where 57-year-old me had got to, she would have been astonished and very happy.

Where do you typically begin your research? Do you have a go-to resource? Has there been anything that you’ve researched for your writing over the years that made a huge impact on you or a novel or series that you were writing? How do you organize your story details across your series?

I tend to begin my research with secondary histories of the period and topic I am studying and then, when I feel I have an appropriate level of understanding, I start to home in on accessible primary sources. I much prefer physical to digital resources, and love to get into an archive if I can. I also find second-hand bookshops invaluable. I often leave with something – printed diaries, letters, newspaper extracts etc. – I hadn’t known existed.

The resource that has probably had the biggest impact on any of my writing is the three-volume, 1,000 page The Lyon in Mourning, which printed primary first-hand accounts by Jacobites involved in the ’45 rising and its aftermath. It hugely informed the characterisation of my novel The Bookseller of Inverness. However, my whole writing career was really sparked by a single entry in the burgh records Aberdeen City Archive that nestled in my head until it popped out again years later, giving me the character of Alexander Seaton. Similarly, the book I have recently finished was inspired by one short document I came across in the Highland Archive in Inverness when I was in looking for something else.

Almost all my research is in A4 spiral bound notebooks. I take copious notes and am constantly sketching out new diagrams of my plans. I am unbelievably low-tech. I go through my notes and index them by hand on old-style index cards, which are extremely useful for quick reference when I’m writing or re-drafting.

Is there a specific scene that you’ve written over the years that you feel especially connected to?

At the end of The Redemption of Alexander Seaton, my character is saying farewell to his old friend and mentor, and his mentor’s words are very closely adapted from the last words someone very dear to me said the last time I ever saw them.

As a historical writer, if you could stand witness to a historical event or walk through a specific time / scene / building or have a frank discussion with one historical figure, which would you choose and why?

I think I would like to have been at Derby and persuaded Charles Edward Stuart and the Jacobite leadership of the ‘45 to strike out for London, rather than turning back in the retreat that ended in disaster at Culloden. Whatever might have happened then could hardly have been worse than what actually did happen.

What three books do you feel are necessary for any book collection to feel complete? What additional one would you add for an author’s library?

Again, sorry to be so conventional but, especially for a British historical novelist – The Bible (King James Version), The Complete Works of Shakespeare, and a really good dictionary – mine is the Chambers one I asked my parents for for my birthday over 30 years ago. The fourth one would depend on the writer’s period of interest.

What can you share about what you are writing now? Or an upcoming release?

My latest novel has been through four drafts and is about to begin being sent out on submission by my agent. It’s set in 1830s Cromarty in the north of Scotland and is about the relationships between members of a reading society there over the period of a year. It’s a new direction for me – not a murder mystery or thriller. Who knows if it will see the light of day, but I had to write it to get it out of my system.

What was the last great book that you read?

Kate Atkinson’s Shrines of Gaiety. Proper story-telling and a sheer joy of a read.

Online tickets for the conference are available:

https://historicalnovelsocietyuk.regfox.com/online

Rebekah Simmers is a member of the HNS UK 2024 conference organisation team. Find out about her novel, The King’s Sword, on her website.

Leave a comment