Apple Gidley asks two pressing questions about historical fiction. Can a novelist write about any topic regardless of their own cultural background? Should historical novels use footnotes?

I write, predominantly, historical fiction but I am not an historian. I do, though, believe that as historical novelists we owe our readers honesty in the facts as far as they can be proven – recorded events and dates, how people dressed, food eaten and so on, all gleaned from research.

Architecture and buildings also tell us stories. A couple of weeks ago I visited Ely, in Cambridgeshire, and after a wander around Oliver Cromwell’s home, came away, still conflicted about his role in British history, but with a greater understanding of life in the 17th century. Closer to a previous home, I tracked down the 1839 Danish census of the residents in our house from which a short story about semptresses emerged to be included in Crucian Fusion.

Where we do have latitude, can take liberties to some extent, is with speech, otherwise our books would be dotted with ‘thous’ and ‘forsooths’. We’d be deciphering Chaucerian-like sentences: ‘A Marchant was there with a forked berd, In mottelee, and highe on hors he sat, And on his hed a Flaundrish bever hat’. An exaggeration I admit, but relevant.

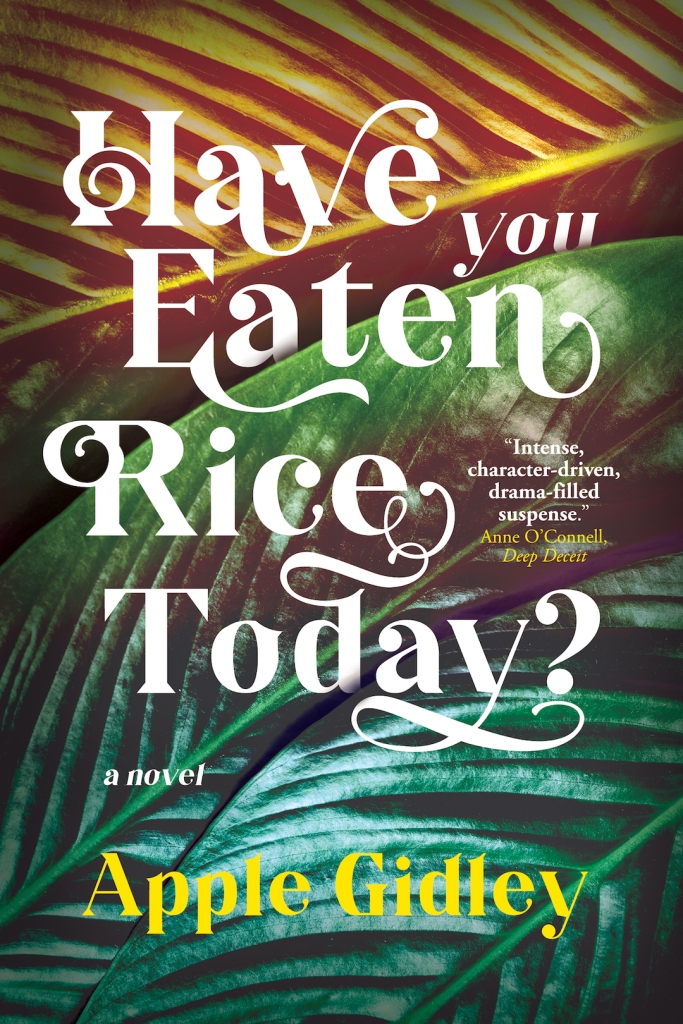

My territory and timescale is considerable. From 1870s Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands) to 1950s pre-independent Malaya, with my current manuscript embracing WWII New Guinea. All of which means my characters are diverse. A vicious Dane, an irascible but delightful West Indian cook, a ‘ bomba’ (black plantation overseer), a headstrong young Englishwoman in Fireburn, and the sequel, Transfer, along with various others. Have You Eaten Rice Today? covers the brutal ‘emergency’ of post-war Malaya when a communist uprising threatened to derail the political push for independence. Brits, Australians, Malays, Chinese and Indians share the pages and through their dialogue their characters and story come to light. Another book, Finding Serenissima, to be published by Vine Leaves Press in March 2025, takes place in Venice with Italians rubbing shoulders with Brits and Australians.

‘Who are you to write this story?’ is a charge sometimes levied at novelists. ‘You are not of this culture, this kinship – it is cultural appropriation.’ Toni Morrison, the great American writer, gave the ultimate comeback by suggesting, ‘If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it’.

I believe as long as the research has been robust and thorough, then anyone can write any story, which in turn might prompt a reader into investigating further. If it happens to provoke questions about a perhaps little-known period of history, or an injustice – consider Émile Zola’s letter, ‘J’Accuse’, to the newspapers – that is a good thing. Anatole France, another tower of French literature, said at Zola’s funeral that ‘he was a moment in the history of human conscience’. What an accolade.

Every reader or viewer extracts what they want from reading a book or watching a movie, but those of us who write the words, whether as a book or screenplay, should not be tempted to dilute the past, to put a gloss on history. History can be ugly and, without being maliciously contentious to modern readers, our characters should reflect those times both in manner and terminology.

The triangular Atlantic slave trade is reprehensible but should be treated truthfully whatever the nationality of the writer, and from whichever viewpoint written. Barry Unsworth’s masterpiece, Sacred Hunger, in which the English author details the greed which drove slavers to often unutterable cruelty, with a counterpoint provided by the essential decency of the Matthew Parris character, is a classic example of balanced writing. It bears remembering that the trading of humans has been part of all civilisations, and continues to this day in one guise or another. The repugnance for historical or current slavery is not the purview of any one person, any one culture.

As I type, my mind wanders to those characters currently living in my head. An Aussie, an Englishman, a raft of Pacific Islanders, and Japanese soldiers all scrambling to survive the swamps and jungle of wartime New Guinea. A term used during the intense fighting, both by Australian military and medics to describe, not in a derogatory manner, the steadfast bravery of native stretcher bearers was ‘fuzzy-wuzzy angels’. I imagine, at some stage, once the book, Annie’s Day, is published (November 2025), there will be pushback from certain quarters, but I will remain true to the vocabulary of the time because it is not only an anecdotal, but also a documented term.

I consider it a privilege to delve into the history of any given country or century, despite research that can make for uncomfortable reading. My stomach churned when I looked at an original newspaper advertisement, crisp and sepia with age, for the sale of men, women and children, followed on the next line by the sale of two billiard tables. People and furniture lumped together as chattels. It happened therefore it can’t be ignored despite the dismay it provokes in modern sensibilities.

Have I manipulated fact to fit the fiction? Of course but, in my defence, rarely and in what I consider a manner that keeps the reader engaged. For example, whilst researching Have You Eaten Rice Today? I found in my father’s papers that he had been credited with finding the communist printing press used to produce their propaganda paper, Battle News. Finding the press is fact but, in the book, the way in which it was found is fiction.

It begs the question should we, as historical fiction writers, have footnotes? It would keep us true to the facts. Or should we be allowed some leeway as long as our interpretation of history is not massaged to create a non-historical novel?

Apple Gidley has led a nomadic life, chronicled in Expat Life Slice by Slice. She is an Anglo-Australian who has lived and worked in twelve countries. Her roles have been varied – editor, intercultural trainer for multinational corporations, British Honorary Consul to Equatorial Guinea, amongst others. In 2023 she relocated from the Caribbean to Cambridgeshire, England – on grey days, she wonders why. With five books published since 2012, Gidley has just begun to call herself a writer. She also pens an irregular blog, A Broad View.

Website: http://www.applegidley.com

Leave a comment